Anne Bremer, Modern Art Pioneer

© Ann Harlow 2018

In 1912 Anne M. Bremer was called “the most ‘advanced’ artist in San Francisco.” In 1916 she was known as “one of the strong figures among the young moderns.” In 1924 she was referred to as an “art apostle,” and later as “a crusader for the modern movement.” Critics often called her work “masculine” and “virile”—high praise at the time, though indicative of the sexism she and her contemporaries were up against. Furthermore, Bremer’s influence was a major impetus toward the creation of one of the first museums to focus on modern art. Yet she has received very little credit for this role in the histories of Californian and American art written to date.

Sometimes Bremer has been classified among the California Impressionists, but given little prominence because most writers think of Southern California as the home of Impressionism in this state. Nancy Moure, in her extensive survey of California art, describes Bremer as an early, “unaffiliated” Post-Impressionist—but only mentions her after devoting much more space to the Society of Six, who have received copious attention in exhibition catalogs and books but who began exhibiting years later than Bremer and did not receive much recognition at the time. Even E. Charlton (“Effie”) Fortune and Armin Hansen, who were probably Bremer’s closest competition as progressive artists in Northern California in the 1910s, have been the subject of solo exhibitions and books. It is time for Anne Bremer to receive more than passing attention as the history of modern art in California continues to come to light.

Spencer Macky, the director of the California School of Fine Arts from 1919 to 1935, said about Bremer in a 1954 interview, “I remember her very well on the occasion of her return from her studies abroad and I remember too the courage with which she introduced to this country and to this coast the new art which has come to be almost so common to you now that you think it has always existed. It took rare courage and foresight and conviction on her part to build the way she built.”

At first glance today it may not be obvious what was so new about Anne Bremer’s art. One might conclude that she espoused modernism rather more than she actually practiced it. On the other hand, it is very likely that our working definition of modernism needs to be expanded in the California context, as it is being expanded in studies of American art in general. The art criticism of the period demonstrates that there was a broad range of representational painting that was considered “modern,” while such movements as Cubism, Futurism and Synchromism were generally called “ultra-modern.” This held true long past the landmark New York Armory Show of 1913, which included examples of these latter trends that were mostly ridiculed even within the American art world. One was considered “modern” if one had an open mind toward experimentation and expression, as opposed to mere realism or prettiness.

Bremer’s work incorporates several elements associated with modern painting. Each of her paintings calls attention to itself as a flat surface holding an arrangement of colored paint, not as a literal representation or illusion of reality. Brushstrokes are broad and distinct from one another, sometimes with areas of unpainted canvas showing through. There is either very little suggestion of depth, or the perspective is distorted or ambiguous. Colors are bold and not always naturalistic. The subject might be figures, landscape, still life or a combination of these, but what was more important to the artist was creating a successful composition and emotional effect. Her works, while individualistic, are sometimes reminiscent of those of Robert Henri and Marsden Hartley, two of the major figures in modern American art. Hartley once wrote that in his opinion Anne Bremer was “one of the three artists of real distinction that California has produced.”

San Francisco in the late nineteenth and early twentieth century, though far removed geographically from the artistic turbulence of Paris and New York, was not exactly a provincial backwater. For one thing, magazines and books discussing and illustrating current art were readily obtained. Most San Francisco professional artists studied in Paris, usually in one of the many private ateliers, the best known being the Académie Julian. Although the training in these schools remained fairly traditional, the visiting artist would also have had many opportunities to see and hear about modern trends at art galleries, independent salon exhibitions, cafes and other gathering places of artists and writers.

One famous location in Paris where very modern art was seen and discussed was the home on rue de Fleurus of Gertrude Stein and her brother Leo, and of Alice B. Toklas after 1913. The Steins were the first significant collectors of the work of Matisse and Picasso, and nearly the first Americans to appreciate Cezanne, who was revered by some artists but barely acknowledged otherwise until the 1920s.

New York, and Alfred Steiglitz’s gallery in particular, is usually considered the entry point for modern art into the United States. But New York is not entitled to claim this role exclusively. The Stein siblings, including elder brother Michael, who also became a modern art collector and salon host, were from the San Francisco Bay Area and maintained ties with friends and relatives there. The 1906 earthquake actually provided San Franciscans access to the avant-garde paintings of Henri Matisse even before any were exhibited in New York. Michael Stein and his wife Sarah, who had been living in Paris, came back to San Francisco to check on their properties soon after the earthquake, bringing with them three Matisse paintings. This was less than a year after works by Matisse and several other artists had created a sensation in Paris at the Salon d’Automne. A critic had said their works seemed like “wild beasts”—fauves—and before long the artists themselves were being called the Fauves. Their work was admired at first by only a few artists and collectors.

After importing the Matisses to San Francisco, Sarah Stein wrote to Gertrude that “since the startling news that there was such stuff in town has been communicated I have been a very popular lady”—and considered crazy for buying it. She doesn’t say what Anne Bremer’s reaction was, except that Bremer told her cousin Albert Bender he must go see the paintings. However, Bremer later told an artist-writer that seeing a Matisse and a Cezanne in the home of “a friend” around this time opened her mind to an entire new world of painting. The friend must have been either Sarah Stein or Harriet Levy, another San Francisco art pioneer and friend of the Steins who went to Paris in September 1907 with Alice B. Toklas, bought Matisse’s Girl with Green Eyes in 1908, and became another important American collector of modern French art.

Anne Bremer studied with Emil Carlsen at the San Francisco Art Students’ League in about 1889 and with Arthur Mathews and others at the California School of Design in 1896-98. Emil Carlsen was one of the leading painters of still lifes in the United States. An 1894 Bremer painting of pansies (left) shows his influence and contrasts with her later work.

Anne Bremer studied with Emil Carlsen at the San Francisco Art Students’ League in about 1889 and with Arthur Mathews and others at the California School of Design in 1896-98. Emil Carlsen was one of the leading painters of still lifes in the United States. An 1894 Bremer painting of pansies (left) shows his influence and contrasts with her later work.

She began painting landscapes in a Tonalist vein, with titles like A Dark Pool and The Gloaming, both exhibited in 1898. The subdued, dreamy Tonalist style, influenced by Whistler, was well represented in Northern California by Arthur Mathews, Xavier Martinez, William Keith, and a number of other Bay Area artists at the time. Bremer’s  The Gray Morning (right), dated 1909, admirably captures the calm quiet of a misty Northern California day and is a classic example of Tonalism. Its elongated vertical format, like a Japanese scroll, may reflect the Japoniste tendencies that were in the air at the time in Europe and America, influencing Tonalists as well as Impressionists and Post-Impressionists.

The Gray Morning (right), dated 1909, admirably captures the calm quiet of a misty Northern California day and is a classic example of Tonalism. Its elongated vertical format, like a Japanese scroll, may reflect the Japoniste tendencies that were in the air at the time in Europe and America, influencing Tonalists as well as Impressionists and Post-Impressionists.

By this time Bremer had decided to explore the art world beyond California first hand. She arrived in New York by January 1910 and enrolled in the Art Students League. In Paris from the summer of 1910 until September 1911 she studied at two forward-looking schools, l’Académie Moderne and La Palette. By the time she returned to San Francisco her style had been transformed.

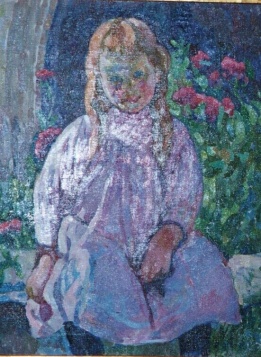

So, although the exposure of Impressionist and Post-Impressionist paintings at the Panama Pacific International Exposition in 1915 is considered a watershed for many California artists, Anne Bremer’s turning point came several years earlier. Shortly after her return from Paris, in March 1912, she had her first solo exhibition at the galleries of Vickery, Atkins and Torrey. Prominently included was her painting of a young girl that had been shown at the Salon d’Automne (below, though not a good reproduction).

While the subject of this painting is fairly conventional, the bold brushwork and colors were ahead of their time for California. Unlike the traditional portrait, there is a vivid outdoor setting competing with the figure for the eye’s attention; unlike the traditional landscape, there is very little sense of depth. All of these characteristics were typical of Fauvism, and Bremer’s work is even more akin to that of the Nabis, whose work was somewhat less extreme in color and more decoratively composed than that of the Fauves.

Porter Garnett wrote in the San Francisco Call that Anne Bremer “has brought us something with which our public is unfamiliar and . . . many persons will be found who are disposed to condemn it out of hand.” He described the painting of the girl as “a noteworthy piece of unaffected dexterity in painting. The sunburnt cheeks, the expression, are managed with a daring that one loses sight of in the perfect success of the thing accomplished.” He also praised Bremer’s paintings of trees, of which Twin Guardians of Point Piños (right) is a good example.

Porter Garnett wrote in the San Francisco Call that Anne Bremer “has brought us something with which our public is unfamiliar and . . . many persons will be found who are disposed to condemn it out of hand.” He described the painting of the girl as “a noteworthy piece of unaffected dexterity in painting. The sunburnt cheeks, the expression, are managed with a daring that one loses sight of in the perfect success of the thing accomplished.” He also praised Bremer’s paintings of trees, of which Twin Guardians of Point Piños (right) is a good example.

In these she combined a gift for two-dimensional design, no doubt learned in part from Arthur Mathews, with a freer approach to color, brushwork and subject matter than her teacher typically used. The documentation that dates both of these paintings to 1912 establishes their early date in comparison to other California paintings, and the fact that the artist died in 1923 is also significant in placing her work well before that of so many well known California “plein air” painters.

The notion that Bay Area artists were held in thrall by Tonalism until after 1915 is debatable; Mathews, Martinez and Keith also produced some bright, cheerful daylight scenes during the 1900-1915 period, as did Granville Redmond and John Gamble, who both started their careers in Northern California although they are often associated with Southern California Impressionism. Nor was Mathews, the rather domineering head of the California School of Fine Arts, particularly anti-modern.

Even as she was being recognized as an avant-garde artist, Anne Bremer painted at least two murals with semi-allegorical female figures. One was the seven-foot-high The Year’s at the Spring (left), painted for a San Francisco hospital. Its line of descent from Puvis de Chavannes by way of Arthur Mathews is clear. As in her landscapes, sinuous, almost Art Nouveau shapes contribute to the design and the artist takes liberties with colors, painting the grass pink.

Bremer demonstrated leadership in the San Francisco art community several times. She was a founding member of the Society of California Artists, organized in 1902 by a group of artists who were dissatisfied with the non-artist governance of the San Francisco Art Association. She was also active in the Sketch Club, a women artists’ group, and while she was president the club organized the first art exhibition in San Francisco after the 1906 disaster. In 1916 she was elected secretary of the San Francisco Art Association and helped it get back on its feet after another period of dissension.

This strong, independent-minded woman embarked on another venture shortly after her return from France. She took a leading role in the creation of the Studio Building, a complex where artists could live and have studios in the same building. Her own apartment, with art studio and roof garden, was there, and adjacent to it was her cousin Albert Bender’s abode. During the year after the earthquake he, too, apparently had a philosophical epiphany. Having created a very successful insurance agency, he became less interested in making money than in using it for the betterment of the community. Bender has been called the greatest philanthropist San Francisco ever had. Although he helped many causes and organizations, his greatest enthusiasms were for books and fine printing, music, and art. He attributed his interest in the visual art of his own time and place to his cousin, Anne Bremer. They had presumably been friendly since he came to the U.S. in 1881, but at some point they fell in love. The intimacy of their relationship was only clear to close friends; the separate apartments kept up appearances as they remained unmarried, whether due to prevalent notions that cousins should not marry each other or for other reasons. It is possible that Anne Bremer was too independent, too much of a “New Woman,” to settle into a conventional family life.

Sadly, however, although Bender lived on in the Studio Building until 1941, Anne Bremer died in 1923. Her art career had been in full swing, with solo shows in Los Angeles and New York, awards in group shows, and growing national recognition, when she developed leukemia. She fought it bravely and turned her creative talents toward writing poetry when she could no longer paint. Bender and friends honored her memory with a scholarship fund and library in her name at the School of Fine Arts, now the San Francisco Art Institute. He went on to be a very generous patron and friend to a great many artists of Northern California and beyond, and his donations of some 1100 artworks formed the original core collection of the San Francisco Museum of Art (later renamed the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art). He also donated numerous artworks to virtually all of the Bay Area’s other art museums. He helped lead the Book Club of California, the San Francisco Symphony, and many other cultural organizations and helped connect them with current trends internationally.

Through her innovative artwork and leadership in the art community, and indirectly through her influence on Albert Bender and the friendships they shared with other artists, Anne Bremer played a key role in the cultural development of San Francisco. What a shame it is that she did not live to see and participate in another two or three decades of that development, and that she faded into an obscurity shared by many excellent artists who are gradually being rediscovered today.

Good day Ann,

My name is Samantha and I hope you have a minute, or two, to humour me.

I bought a painting, signed A(?) Clifford Bremer a couple of years ago at a second hand market (in port Elizabeth, South Africa) and tried tracking down the artist with no luck. A couple of days ago I read an article about how woman painters were not represented in art history and it dawned on me that perhaps I should be looking for a woman and not assume the male name of Clifford was the artist actual name.

The style is in keeping with Anne Bremer. The painting came unframed with nothing on the back for any more clues.

Any chance there could be a connection?

It appears I can not add photographs in this comment box. Let me know if you would like to see them.

The painting is impressionistic (but I am no expert!) and of two trees framing a seascape with a pier and then hills beyond that. Could be west coast California could also very well be Mediterranean.

Hope I sparked some interest 😀

Thank you for time, have a good day further.

Kind regards,

Samantha

Hello Samantha,

I’m sorry, I don’t think I ever saw this until now! It’s a good hypothesis to figure your painting may have been by a woman, but I’ve seen no evidence of the name Clifford being associated with Anne M. Bremer, so a connection is very unlikely. I just checked Askart.com and there’s nothing similar there either. Maybe it was a South African artist.

Ann